MACROECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS OF A CASHLESS SOCIETY: OBSERVATIONS FROM CHINA AND SWEDEN

Most people are very familiar with the benefits of a cashless society by now. Hardly a day passes without the media around the world reminding readers of how e-payments can bring about a decrease in the transaction costs that are associated with the handling of cash, or how businesses can gain consumer insights from data collected from e-payment transactions. Equally, most are also cognisant of the dangers of socioeconomic exclusion in a fully cashless society. For people who cannot afford mobile phones or who cannot open bank accounts for one reason or another, it means not being able to make even simple transactions like buying food or other basic necessities.

But there are deeper implications to a cashless society beyond just faster transactions and attractive reward point systems that an e-payment platform enables. These implications are not necessarily good or bad, but they should be better understood.

Given the borderless nature of e-payments and indeed, of business in general in today’s global landscape, it would be prudent to heed the debates surrounding going cashless in other parts of the world.

In the first of a three-part series on the wider context of cashless societies and what it ultimately means for Singapore businesses, this article looks at the debates in two countries – China and Sweden – often held up as standard-bearers of the e-payment revolution. In particular, we focus on the issues surrounding the over-dominance of e-payment service providers, the possibilities of central bank-issued digital currencies, and the link between cashless societies and the negative interest rate policy.

WHY CHINA AND SWEDEN

China is the world’s biggest marketplace for cashless payments by virtue of its gargantuan population of over a billion consumers.

Sweden is expected to become the world’s first cashless country by 2023. Because its achievements in e-payments are less often trumpeted in Asia compared to China’s, this may come as a surprise to many in this part of the world. After all, Sweden’s smaller population of around 10 million makes it a much easier society to rid itself of cash, whereas China would have to contend with significant disparities between its coastal and interior regions.

China: Implications of the Alipay-WeChat duopoly

Some Singaporeans believe that the country’s e-payment landscape is confusing because there are too many options.

Rather than being an accident of nature, this multiplicity of e-payment options in Singapore is in part because the government has “deliberately taken a different approach so as to allow more competition and innovation in the payments space”, according to Ong Ye Kung, a board member of the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), in his keynote address to the Association of Banks in Singapore (ABS) in June 2018. Mr Ong is also Singapore’s Minister for Education. “Having one or two players dominate the market brings short-term convenience to consumers,” Mr Ong said. “But in the context of Singapore, there will be significant downside risk in the long term due to a lack of competition, especially when the dominant player wields significant market power, and owns all the transaction data and customer information. Over time, this can slow down the rate of innovation, and give rise to the risk of unfair pricing for customers.”

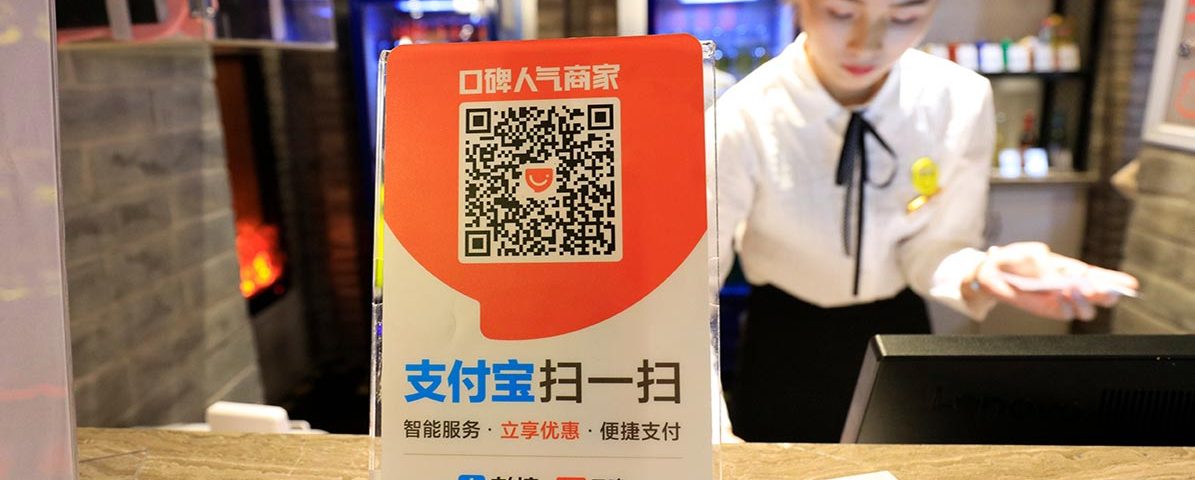

Mr Ong made specific reference to China, where Alipay and WeChat effectively hold a duopoly over the e-payment market, commanding 54% and 19% of market share respectively. Moreover, their dominance goes beyond China – they have been aggressively courting the Southeast Asia market for remittances for instance, and they are also making inroads in Europe.

The issue of a lack of innovation does not seem to figure in China’s e-payment landscape or, at least, not yet. But the Alipay-WeChat duopoly has been formidable enough to cause concern for the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank.

Since June 2018, the PBOC has required online payment companies to channel payments through a new clearing house. This has effectively forced Alipay and WeChat to share their transaction data with their smaller rivals, thus gradually breaking up their duopoly of the payment market.

Some commentators have characterised the PBOC move as a “power grab” after large state-owned banks complained that third-party providers like Alipay and WeChat were taking their deposits. Nevertheless, the PBOC had underscored how the two e-payment companies have not always paid interest to their users despite generating huge returns on the large amounts of money they sit on. This is, in no small measure, because of the lack of real competition in the payment landscape.

Others have pointed out that a central bank like the PBOC needs to have control of the money supply to halt any destabilising outflows of capital, a situation in which China found itself in late 2017. This at least explains in part the action taken by the PBOC.

Sweden’s e-krona: Central bank-issued digital currencies

One of the key roles of the central banks in modern times is to issue bank notes and coins for public use, as part of their mandate to maintain monetary and financial stability. (In a few places like Hong Kong, banknotes are issued by commercial banks like HSBC owing to historical reasons, but even that is a process subjected to the regulation of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the territory’s central bank.)

If everyone were to stop using physical cash, they would have to depend much more heavily on the private sector to get access to money and payment methods. That carries credit risk. Furthermore, in a crisis situation, it would not be easy to force the private sector to take an active crisis preparedness responsibility to stabilise the whole payment market. If the current trend towards complete cashlessness reaches its endpoint, what should central banks do?

One option is to simply leave the whole responsibility of issuing currency to the private sector, as in the days before central banks took on that role. The government could then find new ways to regulate and supervise the payment market, so as to ensure a safe, efficient and inclusive payment system.

Another option is to compel traders and banks by law to accept cash as a means of payment. Chinese authorities have recently cracked down on merchants who refuse to accept cash payments because of the ubiquity of e-payment services, but this is not the case in Sweden.

Yet another option, which is the focus of our discussion here on Sweden, would be for the central bank to issue money in a digital form, as a complement to cash, that is, a central bank-issued digital currency. The Riksbank, Sweden’s central bank, has proposed the e-krona (named after the krona, the Swedish currency). It would have a one-to-one conversion rate with the ordinary krona, and would be a government-guaranteed means of payment without credit risk. Additionally, this would benefit competition and options in the payment market. The e-krona could be held in an account at the Riksbank or stored on a card or a mobile phone app for use.

The Riksbank is at pains to emphasise that this is not the same as a cryptocurrency, which is not issued and regulated by a state institution. The e-krona will not be dependent on the distributed ledger technology.

Other central banks such as the Bank of England have said they are studying the implications of a central bank-issued digital currency like the e-krona, but have no plans at present to introduce it.

Such an innovation like the e-krona would also present new possibilities for central banks, which brings us to the next point on the negative interest rate policy.

GOING CASHLESS: FACILITATING THE NEGATIVE INTEREST RATE POLICY

The existence of cash prevents central banks from cutting interest rates much below zero. This is because for depositors, it would mean paying to keep their cash savings in a commercial bank account. They would therefore want to withdraw as much of their cash as possible. Doing so would spark a substantial outflow of bank deposits, which would be destabilising. This is why interest rates do not generally go below zero – a policy problem known as the zero lower bound on interest rates.

If a country has a dual currency system comprising cash and a central bank’s reserves denominated in an electronic currency like the e-krona however, it would be possible for a central bank to slash interest rates to below zero, while keeping the interest rate for cash separately above zero.

But why would it be desirable to cut interest rates to below zero in the first place?

It has been 10 years since the global financial crisis of 2008-2009, during which central banks in many advanced economies set the interest rate very close to zero and kept it there. This was to disincentivise depositors from keeping their money in the bank and to spend it instead, thereby stimulating the economy through consumption. However, the recovery of the global economy has been very slow and fragile. More precariously, this situation also means that central banks would have no more room for manoeuvre – to further cut the interest rate – if another severe recession hits. Central banks have been debating ideas to remove the lower bound on interest rates to counter cyclical downturns.

In Singapore, however, MAS does not use interest rates as its tool to set monetary policy like most other central banks. Rather, MAS pegs the exchange rate of the Singapore dollar to a basket of undisclosed currencies to achieve that same purpose. This is because Singapore has a small population and is an open economy that depends heavily on trade, as explained by MAS.

The benchmark interest rate used in Singapore is the Singapore Interbank Offered Rate (SIBOR), which is set by ABS on a daily basis based on submissions from a panel of banks. Interest rate movement in other countries do still influence SIBOR.

“NOT FORCING A CASHLESS SOCIETY”

In the same speech that Mr Ong gave to ABS in June 2018, he had said that the “aim is not to force a cashless society, but to enable everyone to enjoy the convenience and efficiency of e-payment”. This should comfortably allay any fears of a dystopian cashless society in some quarters. It also signals a well considered approach by Singapore towards addressing a major trend disrupting the global economy.

Amid the excitement of a vision of a technological future with faster payment transactions and shopping rewards, some of the fundamental macroeconomic implications of cashless societies should not escape our consideration.

This article was first published in IS Chartered Accountant on May 2019. You can read the original version here.

Loke Hoe Yeong is Manager, Insights & Publications, ISCA.